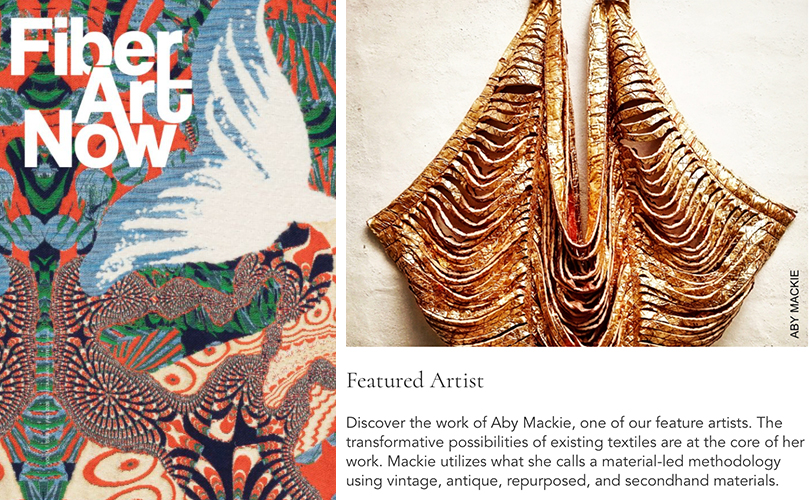

Off to a good start in 2026 — we’ve brought four interesting works to you attention in January.

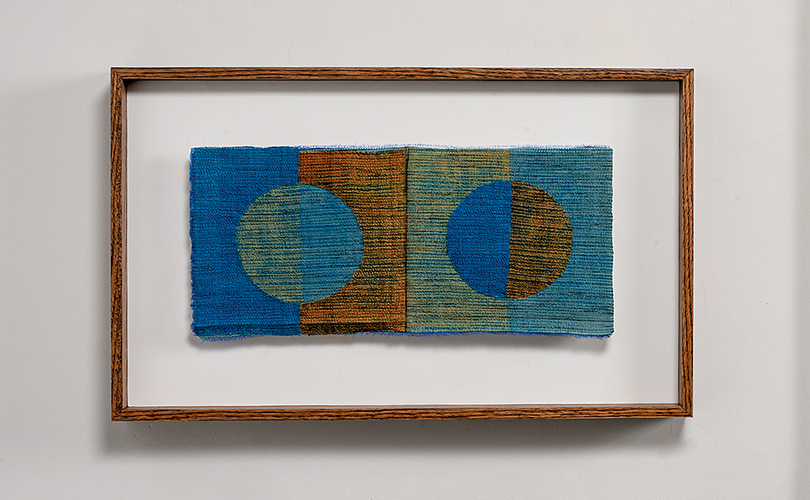

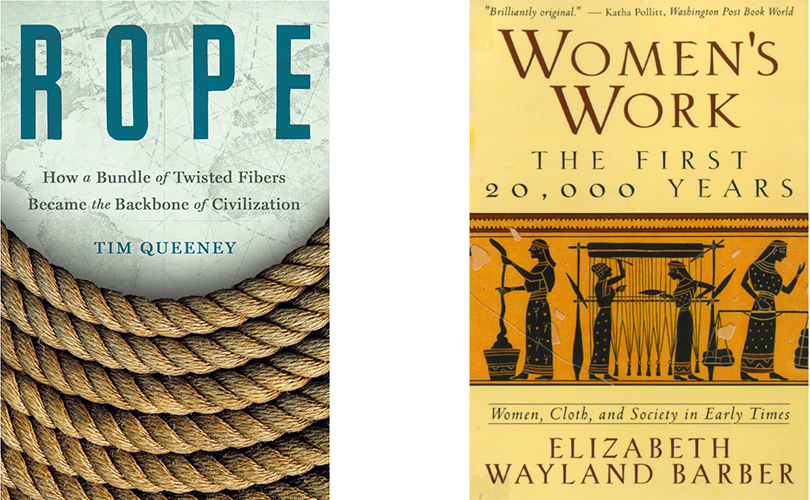

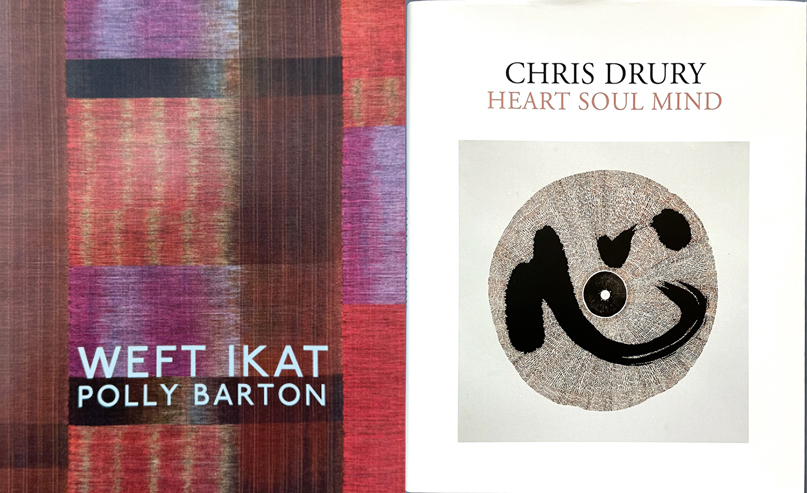

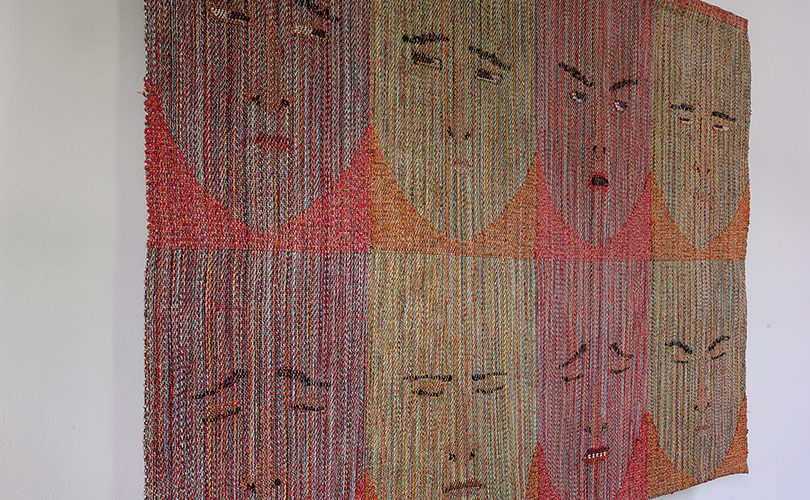

We began with Polly Barton’s Salvia Sclarea (Clary Sage). In 1978, Barton went to Japan as an exchange student where she visited a weaving studio filled with incredibly colored dyed silk. She returned to Japan in 1981 to study weaving at the Oomoto School of Traditional Arts where she discovered that weaving was her calling. She learned silk weaving from the man who warped the looms of living national treasure Fukumi Shimura. As Barton developed her artistic process, she realized that seeing how painter Helen Frankenthaler — for whom Barton had served as an assistant — impregnated her canvases with pigment, gave her “permission” to build up layers of color in her woven ikat works.

In Salvia sclerea — which inspired the title of this piece is the herbaceous plant clarey sage. This work incorporates an image of the plant that moves in and out of view depending on thow the light hits it.

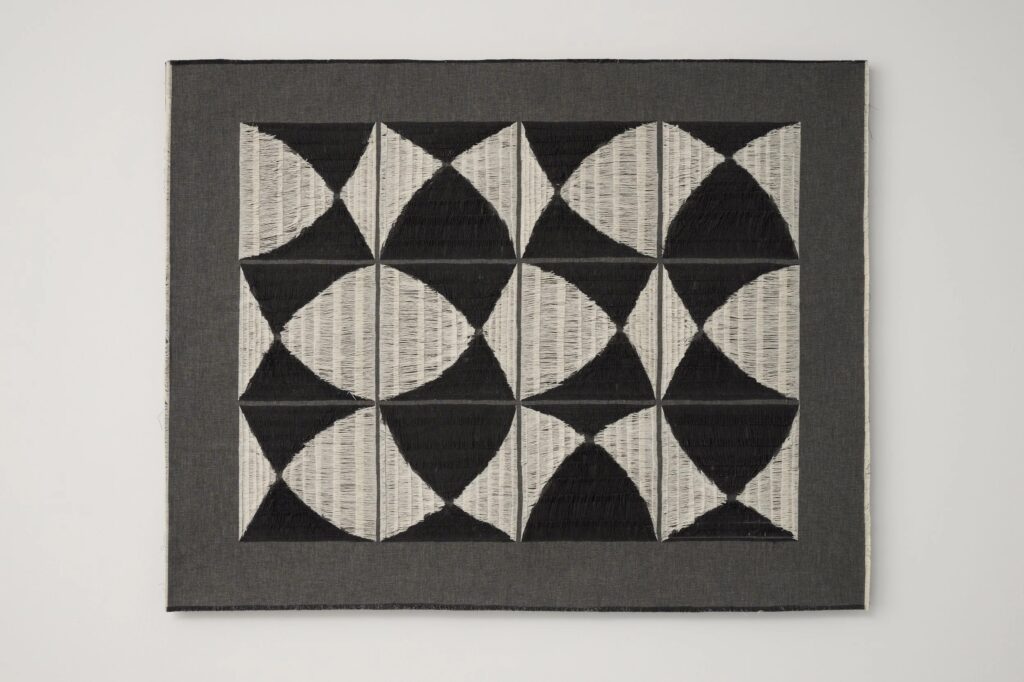

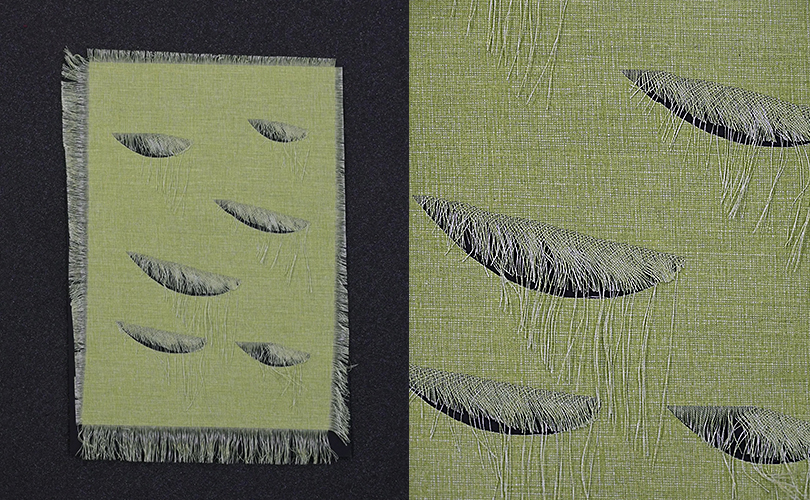

Another work that connects with Nature is Laura Foster Nicholson’s Being Here. Bees are a metaphor for the soul, Nicholson says. Her work Being Here, is from a series of works involving bees and bee hives. Nicholson often reflects gardens and scenes of domesticity in her tapestries. “I have been a beekeeper, and always felt that it was magical and a true privilege to don a bee suit and stand among thousands of busy, humming honeybees. Being Here is the culmination of a body of work about moving through pain to the state of grace that is acceptance. The orb of shimmering insects represents the final opening up to the transformation.”

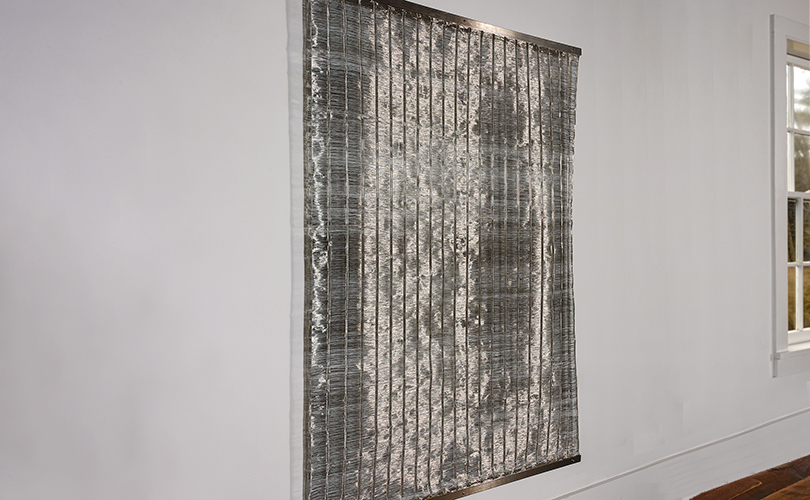

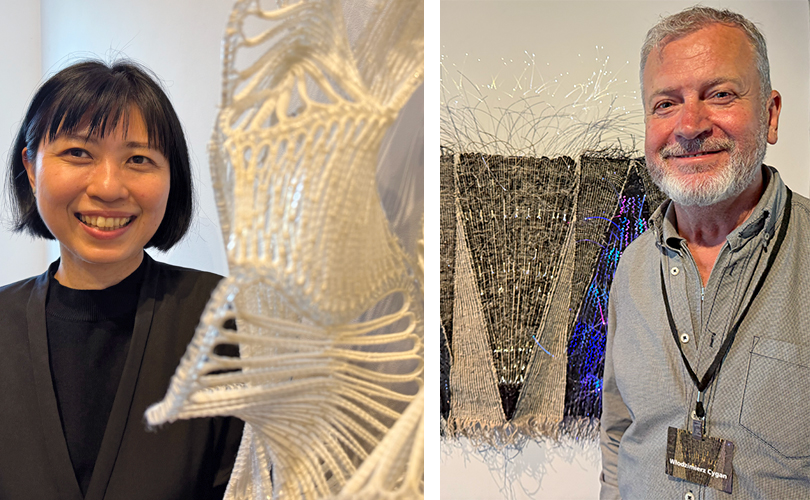

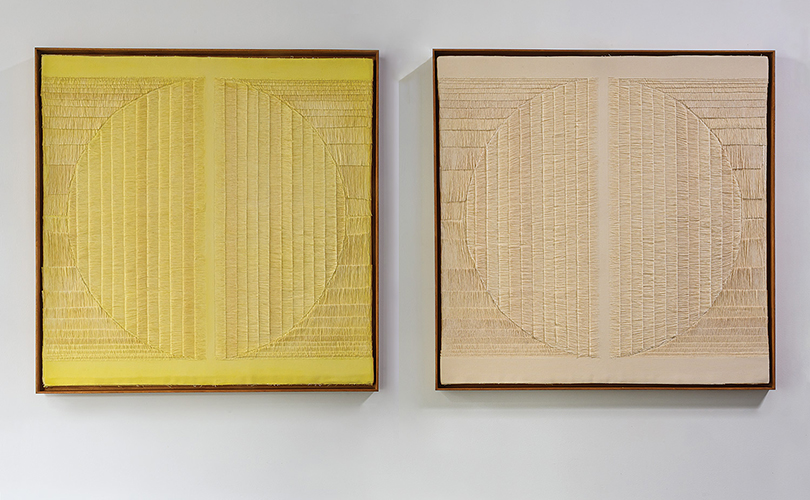

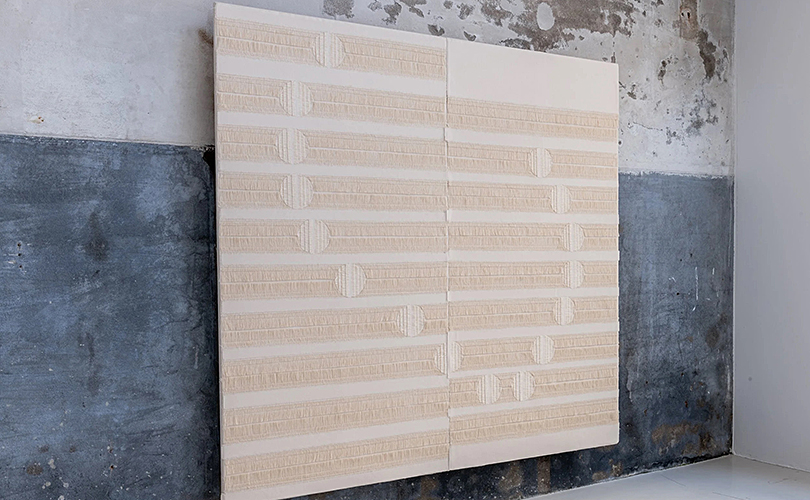

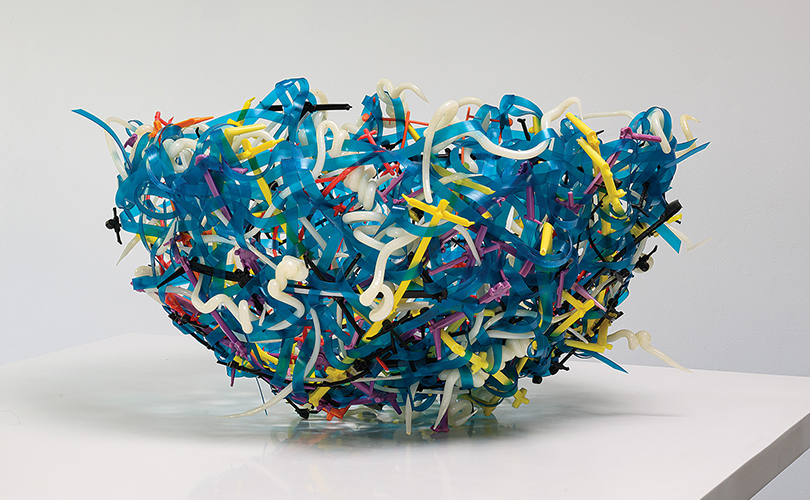

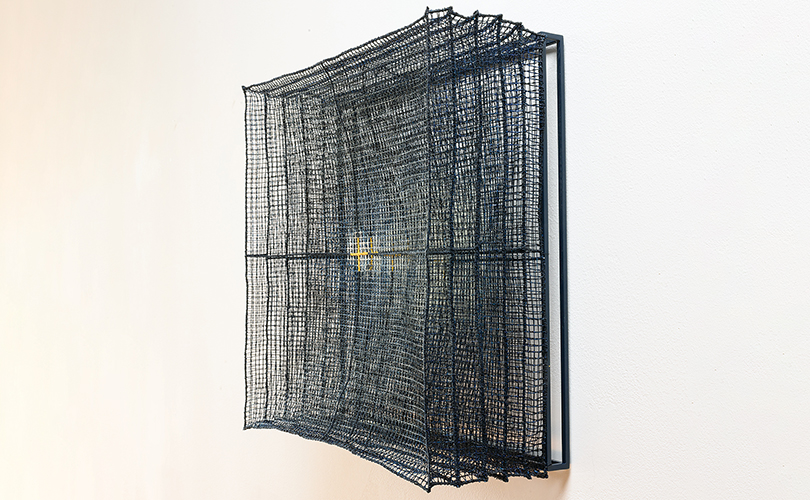

Yeonsoon Chang has created an eco-friendly resin to use in creating sculptural works of hemp and polyester mesh. Recurring themes in Chang’s work include time, space, and the myriad relationships that intertwine them. Chang’s process requires 12 complex and meticulous steps, including refining, dying, ironing, and sewing, all of which require considerable mental focus. She considers it her calling to bring to life the spirit of Korean craft, allowing it to breathe and resonate through works like Matrix III-201612. Chang was a Loewe Foundation Prize nominee and the first Korean artist to have her works acquired by the renowned Victoria & Albert Museum in the UK. Her work was also featured in the Cheongju Craft Biennale in 2025.

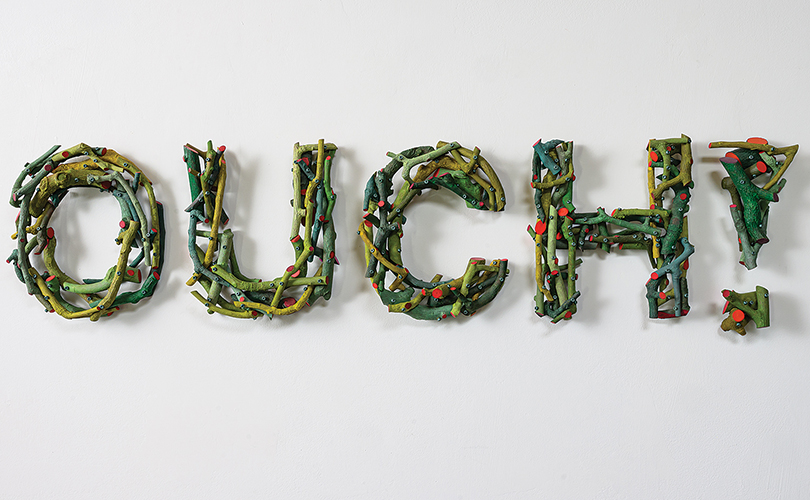

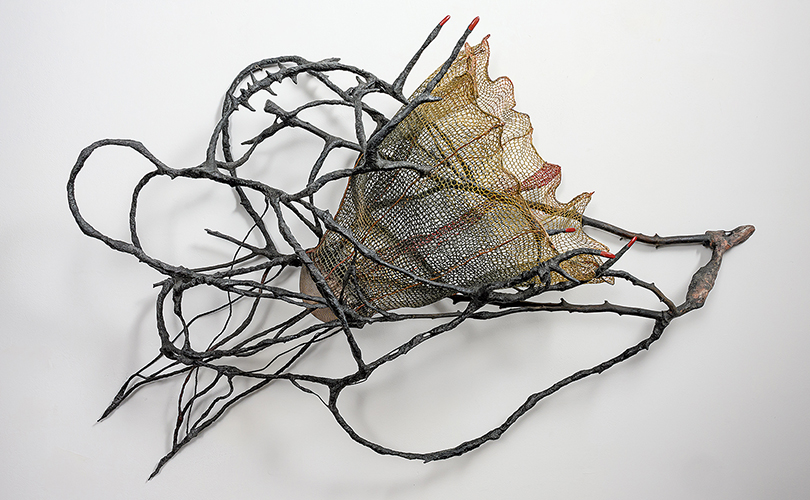

Inside-Outside by Dorothy Gill Barnes is an excellent illustration of the artist’s remarkable way with wood (the name of browngrotta arts’ 2023 monograph, Dorothy Gill Barnes: A Way with Wood, in fact). Bark—from pine, spruce, elm, basswood, mulberry, and many other trees—played a seminal role in her work. She cut or tore bark in strips and wove it into basket- or vessel-like forms, folded it into rectangular boxes and windows, pulled it back like a banana peel, and wrapped it around rocks. To add tension and contrast, she paired bark from different species of trees, different textures of bark from the same tree, and peeled or unpeeled surfaces. In Inside-Outside, she has paired wood strips with bark and strips without bark, weaving them to form the base and stitching the strips to form the sides.

More works to come in February!